|

Christina was failing my class. She had stopped doing the work and I wasn’t making much headway when I reminded her about missed assignments. I suspected this was a case of senior slump, and I called her mother and asked for a conference.

I showed Christina and her mother my grade book and walked them through everything that was missing. Christina’s mother asked her what was going on, and Christina looked at me and quietly said, “You’re a racist.” My immediate reaction was defensiveness and disbelief. Outside of school, I was deeply in love with the novels of Toni Morrison and Gloria Naylor and the poems of Gwendolyn Brooks and Lucille Clifton. Inside school, I had made an effort to supplement the standard English curriculum with more Black authors. So at the conference, I came back to the gradebook and argued that this was simply a matter of doing the work--the same work that was required of every other student. Twenty-five years later, I see this episode quite differently. I see how I should have responded to Christina’s statement with curiosity instead of defensiveness. Christina was the only Black student in my Creative Writing class, which had no required curriculum and gave me complete freedom to design and conduct the class in any way I liked. I prided myself on my relationships with students in this class and the little creative community I thought we’d built. Was it possible that Christina felt excluded from that community in some way I wasn’t aware of? Did she sense some difference in how I related to her compared to her classmates? These are the questions I should have asked at the time. I regret that I did not. Teachers and school leaders--in fact, the whole school staff--have to create environments where no student feels invisible, dismissed, or less than. A student who feels this way will either act out or check out: they’re mentally (and sometimes physically) missing in action. Disengagement is a significant problem in our nation’s schools. One measure of this is regular Gallup polling, which reveals that less than half of US students feel actively engaged at school. Gallup senior editor Jennifer Robison writes with some concern that “actively disengaged students are nine times more likely to say they get poor grades at school, twice as likely to say they missed a lot of school last year, and 7.2 times more likely to feel discouraged about the future than are engaged students.” This stuff matters, and I’m bringing it up now because I believe school and classroom culture are fundamentally important to supporting students’ ability to regain lost ground after the pandemic, move forward and thrive. When a student disengages, it’s the job of school staff to get curious--as I should have, all those years ago. When we get curious, we’ll find many reasons why students are checking out: 1. Like Christina, they perceive that they’re operating at a disadvantage due to their race or ethnicity (and often actually are.) In one of his books, the educator and academic Christopher Emdin describes visiting a science classroom where a Black student had pulled his hood up, made a pillow of his arms and slumped over his desk. When Emdin spoke to him after class, the student explained that he had raised his hand several times, was repeatedly passed over by the teacher, and decided to give up. Black and Middle Eastern/North African (MENA) students in particular rank their schools more poorly when it comes to teacher-student relationships, cultural and linguistic competence, rigorous expectations, engagement and school safety. 2. They are subtly discouraged from, and sometimes actually counseled out of, enrolling in the advanced level classes they’re capable of. Students with disabilities, and in particular twice-exceptional students, may experience this in APS and elsewhere. 3. They’re not being offered opportunities for higher-order thinking and quality interaction. In a 2019 English Learning program evaluation for APS, researchers concluded that 90% of lessons observed at the secondary level didn’t demonstrate academic rigor. The same evaluation noted that 11% of APS EL students had been receiving services since kindergarten and that 43% of high school students at the lower (WIDA) English levels 1-3 were dropping out. 4. Girls are receiving the message that they are less capable than boys. Sometimes this shows up in the ways teachers address girls: with a potentially patronizing “honey” or “sweetie” while boys are recognized by name, or with an inordinate number of comments focused on their appearance and not their ability. It may be the result of unconsciously held beliefs: one researcher describes a female teacher who told him, “Now, I don’t even understand why you’re looking at girls’ math achievement. These are my students’ standardized test scores, and there are absolutely no gender differences. See, the girls can do just as well as the boys if they work hard enough.” He writes, “Then, without anyone reacting, it was as if a light bulb went on. She gasped and continued, ‘Oh my gosh, I just did exactly what you said teachers are doing,’ which is attributing girls’ success in math to hard work while attributing boys’ success to innate ability.” 5. Students may feel like outsiders at school because of their political or religious beliefs. A few years ago, I had the opportunity to listen to a youth-led discussion among students enrolled at various public and private high schools in DC. One student from Georgetown Day School described how uncomfortable he felt as a political conservative attending what he perceived as an overwhelmingly liberal school; it was easiest, he told us, for him to keep a low profile and not say too much in class. This is just a partial list, but you get the idea. Kids, just like adults, will shut down and check out when they find themselves in a toxic work environment. But it’s harder for them to quit and go look for another opportunity. When we talk about what’s essential in APS, I will argue every day of the week that our must-haves must include things like professional learning that includes implicit bias training and school culture surveys and analysis. We absolutely have to have rigorous, research-based curriculum, but the best curriculum in the world won’t engage a student who, like my student Christina 25 years ago, has already absorbed a message that she doesn’t count and shouldn’t try. When I started kindergarten in Fairfax County in 1974, only six years had passed since the U.S. Supreme Court finally ended state-sponsored segregation of Virginia’s public schools.

1968’s Green et al. v. County School Board of New Kent County, Virginia was the last vestige of Massive Resistance—the formal, government-sanctioned opposition to public school integration led by Virginia Senator Harry Byrd that swept across the American South in the wake of the landmark 1954 decision Brown v. Board of Education. Although in 1955 the Supreme Court ruled that schools should be integrated with “all deliberate speed,” it took Virginia another 13 years to do so. Aided and abetted by the state government, many counties in Virginia, most notably Prince Edward County, closed their public schools rather than integrate them. In 1959, the all-white county board sold the school system’s buildings and equipment for $1 to local business leaders who had established a new, all-white private academy. The Academy’s trustees depended on state-funded tuition vouchers that fueled the private “segregation academies” across the Commonwealth until the Supreme Court outlawed this funding in 1969. In the 1970s as I began school, backlash against federally-mandated integration was very much apparent. For example, white students burned crosses at schools attended by Black students, including in nearby Alexandria; in Winchester, where I would later teach, local officials had to call in state police to quell a race riot at the high school. Everything Old Is New Again Virginians who think about it longer than a nanosecond will feel a strange sense of deja vu when they hear Glenn Youngkin stoking racial unrest at his rallies. At a rally in Leesburg—one of the last places in America to desegregate its public schools in the late 1960s—Youngkin intoned, “Our curriculum has gone haywire. So on day one, we are going to ban teaching critical race theory in our schools.” When Glenn Youngkin talks about “banning critical race theory,” what he really means is that we should not be teaching about state-sponsored racism in Virginia, past or present. Never mind that many of our Black students’ parents and grandparents experienced segregated schools firsthand, or that the lack of educational opportunity for Virginia’s Black students has had life-altering and multigenerational consequences. And it’s not an accident that while he is fanning racial fears, he is also peddling privatization and vouchers. It could be 1959 in Farmville, Virginia. Candidates like Glenn Youngkin are cynically manipulating voters in what some are calling “the New Massive Resistance”—and Virginia is Ground Zero. It probably doesn’t come as a surprise that I support Terry McAuliffe. After all, I am running for School Board as the endorsed candidate of the Arlington Democrats—but that does not mean that I believe Democrats have always cornered the market on great education policy and investment. I am also running as a product of Virginia’s public education system—the one afforded to white students—from kindergarten through graduate school. I love my state, but that does not mean I have to disavow the painful parts of its past and present. Finally, I am a lifelong advocate for public education. And that doesn’t mean ignoring the system’s flaws; it means tirelessly committing to making it better because I believe our students and our democracy depend upon it. If you believe that, too, and if you believe Virginia deserves a more ambitious and inclusive and hopeful future than the one being peddled by Glenn Youngkin, I hope you’ll join me in voting for Terry McAuliffe next week. We’re now in our fourth week of the school year, and we all basically agree that we want to do everything we can to help students succeed. Recover. Be safe. Catch up. Connect. Thrive. Whatever phrase you’d supply, our intentions are aligned.

But here’s the thing: “doing everything we can” requires people power, and we’re not fielding a full team. We’re still short 65 certified employees (basically, those folks who work directly with students in schools every day and have a professional license to do so) and we’re trying to fill 74 open positions for support staff. I’ve been looking at the job postings since early August and I’ve watched the numbers fluctuate from more than 140 certified staff job openings down to about 50 last week, and now back up again to 65. Our vacancies include (as of 9/22/21):

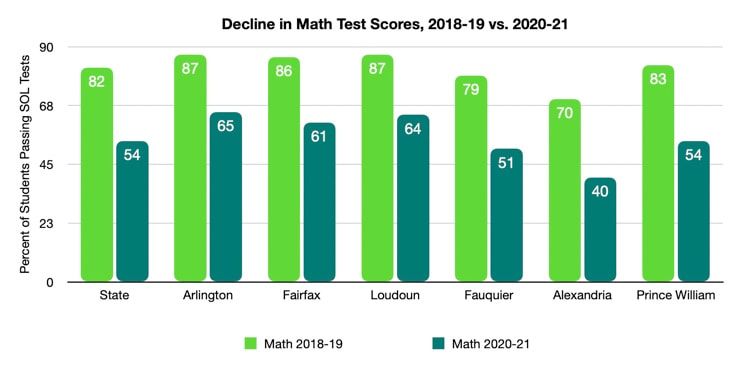

This is no criticism of APS—this is true basically everywhere right now. You can Google “teacher shortage 2021” and name a state and you’ll read pretty much the same story. The need is particularly acute in special education: 48 states are reporting shortages for the 2021-22 school year. And when teachers have to quarantine, there aren’t substitutes to fill in, forcing many school districts to close classrooms and revert to remote learning. Nationally, we saw this coming: experts were writing about a looming teacher shortage years before COVID. Enrollment in teacher preparation programs dropped by more than a third in the decade leading up to the pandemic. COVID hasn’t helped: in a national RAND survey last March, 42% of teachers reported that they had considered leaving or retiring during the 2020-21 school year. Of these, slightly more than half say it was because of COVID-related job stress. A May 2021 survey by the National Education Association yielded similar data. NEA members reported concern about their physical health and safety—with only one-third of respondents saying their schools had adequate and safe ventilation—and their mental health, with 41% of respondents reporting that they were “not sure” if their districts have any plans in place to address educator anxiety, depression and burnout. What will we need to do in Arlington to fill vacancies and keep the staff members we have? 1. Ask them—and really listen to what they say. We don’t need to guess what will motivate teachers and other staff members to work in our schools. They’ve told us. For example, we have data from the Your Voice Matters survey (more than 3,500 staff respondents). Only 37% responded favorably to questions about their voice in decision making and opportunities for professional learning. Only half responded favorably to questions about their safety at work and the quality of home-school partnerships. 2. Make this a budget priority for FY23. As it does every year, this October the School Board will provide direction to APS leaders as they begin developing next year’s budget. I believe this issue needs to be front-and-center. For the first time in Virginia, our educators are empowered to engage in collective bargaining with their school districts. If I’m elected I know I will be on one side of this bargaining table and so I probably shouldn’t say this, but: APS, don’t mess this up. Without a great staff, all the rest is window dressing. 3. Get committed and creative when it comes to staff mental health and well-being. Educators can’t support students’ well-being if their own tank is empty. Ask staff what would help (see #1 above) and then let’s do it. In other school districts, this has meant creating helplines; establishing tap-in/tap-out practices; developing shared agreements about how staff can support each other (e.g., don’t send work-related emails over the weekend; sit with a new staff member; etc.); and more. Additional, helpful resources on this subject include this May 2021 Education Week article and a Relationship Mapping Tool from the Harvard Graduate School of Education. I’ve worked in schools and to support schools for most of my adult life. I know that education is a deeply social and human enterprise. Let’s take care of those humans we’re trusting with the education of our kids. It happened. Both of my kids are out the door this morning and back in school five days a week with most of their classmates. (A shout-out here to those students who need to or have chosen to stay virtual for the time being--I am cheering for your strong start, too.) What will make for a great first week for all of Arlington's students? What should parents expect and what can they do to support success for their children and their school? Based on my experience working in education, recent reading and community conversations, here's what I am hoping to see this week: 1. Time for teachers and students to get to know each other. Students (and adults!) do their best work when they are in environments where they feel safe, understood and valued. David Bromley, a school administrator in Philadelphia, shared with me a few years ago that his staff accomplishes this through substantive advisory periods: “You get to know your students in a way different from anywhere else… Building community comes back to intentional use of time and what message you are sending to kids about how their time is used each day. Saying it’s a priority and really making it a priority is key." Denise Funston, a principal working in Missouri, once told me: “I don’t care if you teach anything the first few weeks of school. I want you to get to know your students and their families. Every successful child has at least one supportive adult, and we take that on as our goal.” To some readers, Denise Funston's comment "I don't care if you teach anything in the first few weeks of school" will sound alarming. Given what we know about students' unfinished learning from last year and their academic needs, it will feel like we should dive right into core content on Day One. I am concerned about students' academic needs, too. It will be essential for schools to carefully assess what each student knows and needs during the first month of school and plan instruction that addresses their strengths and gaps. That said, I am suggesting two things for families' consideration. First, student learning will be accelerated and deepened by building on a strong foundation of knowing each student well. This makes sense to me as a former teacher: if I know my students, I can design instruction that appeals to their interests, which will deepen their engagement. My son, for instance, loves golf and classic cars. After struggling in Algebra last year, he's going to need some help in math. I can guarantee you that he will be 100% more interested in math if we can show him how it relates to restoring a car or making a birdie on a golf course. Second, we are not alone in seeing significant declines in standardized test scores in 2020-21. Take a look at our neighboring districts and the state average in math SOL scores, for example: I'm not arguing that we shouldn't be concerned--rather, I'm arguing that we should keep in mind the context. Across the state and nationally, we are in the same boat. There is a gap between the system we designed--which assumes a certain type of instruction--and what we were able to actually provide during a prolonged, international emergency.

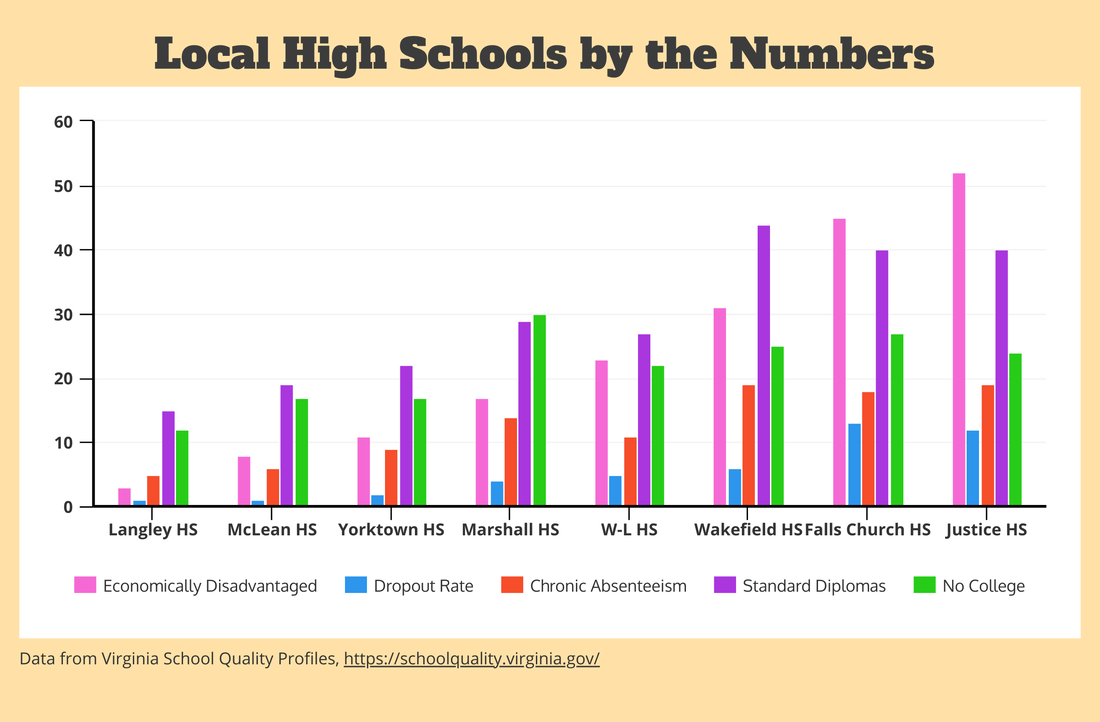

2. Identifying students' mental, emotional, and physical needs. We know that students (and adults) have trouble learning if they are affected by trauma, economic insecurity, food insecurity, or other significant stressors. School staff, and in particular our counselors, social workers and psychologists, will need to proactively check in with students individually and in small groups to understand what students have experienced and what they need. Universal screening for mental, emotional and social issues will be extremely helpful. Close collaboration and frequent communication with families will be helpful. Joni Hall, a school principal in Tacoma, Washington, told me a few years ago about how each staff member at her school serves as a mentor to a small group of students: "The mentor knows and cares about each child in [their] group… if there’s a problem, the teacher will contact the mentor first, before administration. Mentors also help families navigate the system. They’ll go meet with parents at homes, McDonalds, wherever they are comfortable. We spend a lot of time on culture and community and personal life." 3. Creating classroom and school norms. I say "creating" instead of "reinforcing" or "teaching" here because it's my hope that schools will take this opportunity to engage students in some meaningful conversation about rules, norms and roles in school. What rules really matter, and why? What expectations ring hollow and could be discarded? Over the summer I read a great article (which of course I can't find at the moment!) about a second grade teacher who creates a list of classroom "jobs" together with her students after they've had the benefit of about a week's worth of school. Students have the chance to observe and weigh in on the parts of the school day that are challenging for them and design roles that will help the day go more smoothly. I think this is especially important this school year. I have joked with friends that my kids have turned sort of feral during COVID (only half-kidding) and have lost their grasp of some of the social norms that normally guide their relationships with peers and adults. I suspect they're not alone. We'll all need a little time to re-learn how to interact with each other. 4. The power of positive communication. This year more than ever, it will be important for families to hear from school staff with positive messages that their students are in good hands. We shouldn't underestimate the power of a positive phone call home to set a strong foundation for teachers and families working together to support students and troubleshoot problems that may arise. This goes two ways: families can start the year by communicating positive feedback, instead of complaints, to school leaders and teachers. A couple of years ago I wrote a blog post outlining some ideas that parents (including myself) could use to communicate more constructively with school staff. I aim to do that this week. Will problems come up? For sure. Do we sometimes need to advocate on behalf of our students? Yes we do. But I've found that it generally goes better when difficult conversations can be placed within a larger context of collaboration and respect. I don't always execute this well, but I'm working on it. So: thank you, ACPD officer who untangled the traffic around Carlin Springs ES and Kenmore MS this morning. Thank you, school bus drivers and nurses and cafeteria workers and principals and parent volunteers, and everyone else who is working to get (and keep!) kids back in school. Here's to a great school year. Last week I got two questions via social media that ask variations of the same thing: How can we understand how our schools are performing relative to other schools in our area or across the country? One questioner simply requested: "Please grade APS as a school district." The other asked, "APS High Schools (Yorktown, W-L, and Wakefield) trail nearby Fairfax schools (Langley, McLean, Marshall, Woodson, Oakton) in SAT scores and all school ranking services (Niche, Great Schools, US News). What do you think APS should do within the next 3 years to remedy that deficit?" School ranking services like Great Schools and Niche pull data from sources like the Virginia School Quality Profiles. (Under federal education law, each state must offer some type of publicly-available "school report cards" and report certain indicators to the US Department of Education.) In Virginia, we can learn a lot about our schools from their School Quality Profiles, including how each school's students perform on the Standards of Learning assessments, how many students are completing advanced coursework and CTE credentials, the percentage of students going on to college, per-pupil spending, the number and type of disciplinary actions taken, teachers' education and experience, and kindergarten readiness. When I look at APS high schools relative to nearby high schools in Fairfax County, using the Virginia School Quality Profile data here's what I'm seeing: These data show what I would expect: schools that have a greater percentage of students from more affluent families generally have more students graduating with advanced diplomas and going on to four-year colleges and universities. I believe this has more to do with the resources these students and their families are able to access than something exemplary happening in certain school classrooms. Middle- and upper-class families are able to foot the bill for many "extras" including:

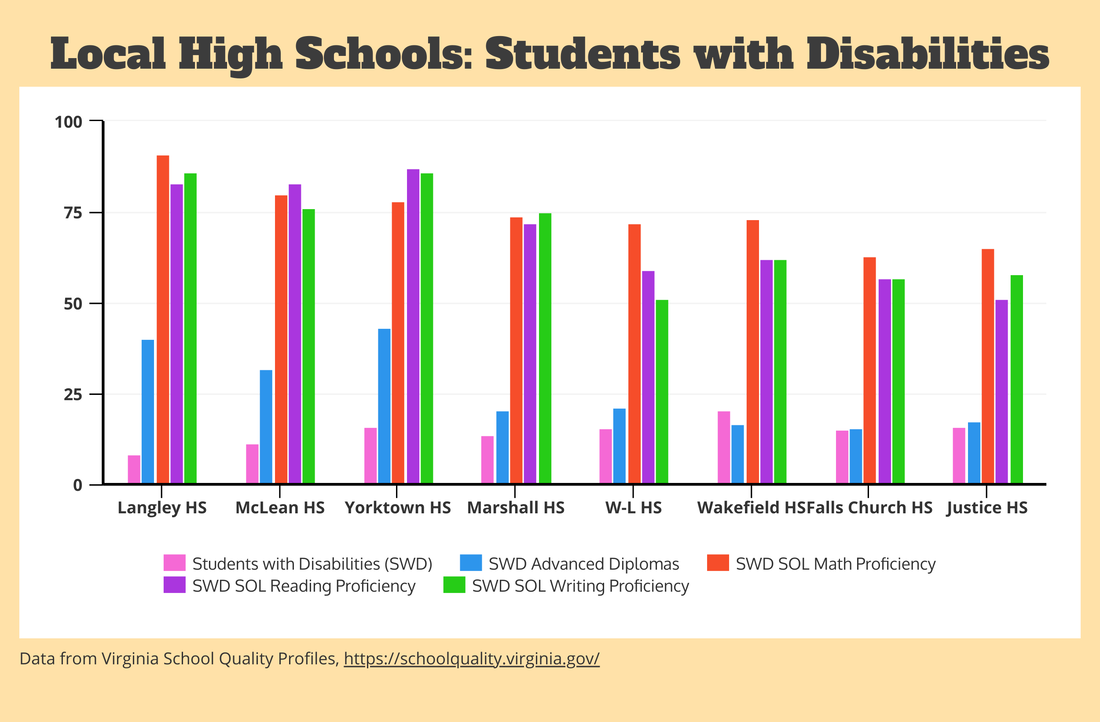

Do these things influence how a student does in school? You bet. Does this mean that it doesn't matter what schools do because the outcomes are predetermined? Absolutely not--but it does mean that indicators of school performance, like those shown in the chart above, are far more interesting when we spot schools that are bucking the trend. For example, the high school in Harlem that has zero dropouts, an 87% college enrollment rate, and a student population that is 77% economically disadvantaged. Or the high school in Oakland whose students are 100% English learners, most having immigrated to the US within the past four years, and 91% economically disadvantaged. 99% of these students are taking classes required for admission into the state college (UC/CSU) system. I also want to note that it matters who is asking the question, "How good is this school?" What's a good fit for one student may not be great for another. For example, if I'm a parent of a student with disabilities, I'm going to want to filter the data in the Virginia School Quality Profiles so that I can focus on how well each school engages and teaches students with disabilities. If I do that, I'll see the following: These data suggest that it might be Yorktown, not Langley, that's the better performing school for students with disabilities: a greater percentage of these students are earning advanced diplomas at Yorktown and achievement on the English Reading and Writing SOL tests are on average higher. (Note that you can also filter Virginia School Quality Profiles to focus on other groups including students who are English learners and students of various races and ethnicities. In my "not-a-professional-data-scientist" review, none of these correlated as closely with overall school performance as did family income.)

Finally, I hope that legislators, education leaders and families will ask for and use more holistic and detailed measures of student success. My favorite "school report card" system is the New York City Department of Education's School Quality Snapshot dashboard. There I can find a wealth of data on each school, including things I can't track in Virginia like:

The NYC School Quality Snapshots are something the district chose to do on top of their state-mandated reporting. How cool would it be if APS and other school districts offered something similar? The ability to expand our definition of "success," transparently report our strengths and challenges, hold ourselves accountable for steady progress, spot the outlier schools that are exceeding expectations in some way and work to scale what they're doing right... that sounds like a great school system to me. Two years ago, the US Department of Justice reached a settlement with Arlington Public Schools after a federal investigation found “several compliance issues” with the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974. The settlement outlined measures that APS would be required to take through July 2022 to improve how it teaches students who are English learners. Since the 2019 settlement, a global pandemic has significantly complicated how we address the needs of students who are English learners. Beyond academics, many of these students and their families have been grappling with food insecurity, job loss, inability to make rent and mortgage payments, COVID-related illnesses and deaths, and more. In Arlington as in other communities, BIPOC and lower-income families have been hardest hit by the virus. Mindful of both the longstanding issues (as described in the 2019 DOJ settlement and other studies) and immediate critical needs, I’ve been reviewing the end-of-year reports from two APS citizen advisory groups: the Superintendent’s Advisory Council on Immigrant and Refugee Student Concerns (SACIRSC) and the Advisory Committee on English Learners (ACEL), which is part of the larger Advisory Council on Teaching and Learning that reports to the School Board. Here are some of my takeaways from these reports, looking to answer the questions “How well is APS meeting its obligations to students who are English learners?” And “How can APS engage, support, and benefit from the experiences and perspectives of immigrant and refugee families and students?” (Note: I understand that “Immigrant and Refugee” and “English Learner” are not synonymous. For this piece, I am focusing on students and families that are both English learners and newcomers to the US.) 1. The need for data, reporting and accountability: Have we improved teaching and learning for students who are English learners? Independent researchers presented detailed findings in a 2019 English Learner program evaluation, and the DOJ identified 38 specific obligations in its settlement with APS. Currently, there’s no public reporting on whether and to what extent we’re gaining ground. This would be something I’d hope to see in an equity dashboard that APS should share transparently with the community in multiple languages. 2. The importance of teachers’ professional learning and culturally relevant curriculum. In its end-of-year report ACEL reminds us that all teachers need sustained professional learning that equips them to work with students who are English learners. At the time of the 2019 EL program evaluation, professional development for “general education” teachers on English language learning was optional, and those who participated indicated a low level of satisfaction with the training. The DOJ settlement required 30 hours of training over three years for core content teachers plus training for principals. The researchers who visited APS classrooms in the 2018-19 school year also found that 90% of the middle and high school lessons they observed did not demonstrate academic rigor. Among parents of students who are English learners, only 59% responded favorably in the APS Your Voice Matters survey that their children’s teachers have sufficiently high expectations—the lowest result of any student subgroup. Low expectations and a lack of academic rigor have contributed to high rates of absenteeism and a dropout rate of 43% in 2019 for students who are beginning or intermediate-level English learners (WIDA levels 1-3). The researchers who spent time in APS classrooms wrote that students who are English learners need to be “motivated by lessons that are interesting, engaging, and applicable to school and other aspects of their lives.” It’s good education practice: students need to be able to relate to and see themselves in the school curriculum. Leaders of the SACIRSC echoed this in a February 2021 letter to the Virginia Advisory Committee on Culturally Relevant and Inclusive Education Practices. They urge state policymakers to address “the history of a broad range of immigrants of color, in addition to enslaved and freed African-Americans, Indigenous Peoples, and Whites.” 3. The importance of Bilingual Family Liaisons: Bilingual Family Liaisons are APS staff members who connect bicultural families and school staff, providing interpretation, translation and other types of support. In its report, ACEL calls Bilingual Family Liaisons “one of the strongest connections between many EL families and their school community” and recommends that these staff members receive more training and collaboration time. Because there is only one Bilingual Family Liaison at a given school, it’s currently challenging for them to identify shared needs and develop shared resources. Additionally, Bilingual Family Liaisons need APS-issued iPads and cell phones so they can help families access Parent VUE, Canvas, and other instructional platforms. The SACIRSC recommends hiring an Amharic-speaking Bilingual Family Liaison. 4. The importance of pro-active and user-friendly communication: APS uses a commercial online service called ParentVUE as its way to share student information with families. The SACIRSC has urged APS to “redouble its efforts to ensure all families know how to access and use ParentVUE and explore what other tools would be more effective.” On Monday, APS sent out a systemwide notice that ParentVUE has been updated and the link to access it will change; the old URL will lead to an error message, further complicating what is already a challenging system for many (including me sometimes!) to navigate. The SACIRSC took the initiative to produce a weekly “What You Need to Know” newsletter last school year in Spanish and English in a format that worked well for WhatsApp users; this group is also advocating for APS to engage via WhatsApp in other major languages. The SACIRSC also recommends the following: “pro-active check-ins to ensure students and their families know about resources and are connected to them as needed. APS should not rely on push-out messaging and assume families’ awareness or understanding.” What could a pro-active check-in look like? Last year many school districts used calls and home visits to check in on students who weren’t showing up for distance learning, and many school district leaders have themselves been going door-to-door over the summer to answer parents’ questions about school safety and help set up vaccinations. When students return to school, pro-active check-ins could include trauma and mental health screenings for all students and regular, protected time for students and families to check in with counselors and advisors. 5. The importance of community collaboration to address basic needs: We need coordinated and effective approaches to hunger, housing, child care, health care, connectivity and more. Fundamentally, this requires collaborative effort across various County agencies, APS departments, and community organizations. Our pandemic response to date provides a valuable case study to examine: How well did we (collectively) do in making sure everyone had food? Were we able to provide adequate child care for essential workers? If not, why not? What would we do differently going forward? In the future, how could we use community facilities and resources more creatively and flexibly? I want to recognize the hard work of the Superintendent’s Advisory Council on Immigrant and Refugee Student Concerns here—its end-of-year summary of the Council’s activities includes the following:

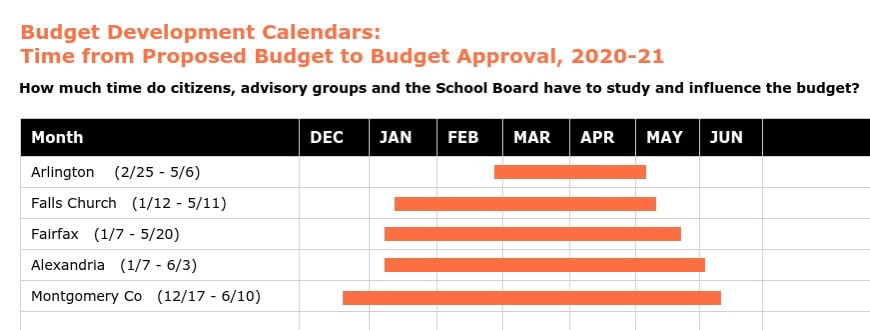

Council members: thank you. I’ve been making the case during the campaign that we need to do more to leverage the incredible knowledge, skills and commitment of Arlington’s citizen volunteers. I offer as one proof point these end-of-year reports that describe the activities and insights of our APS citizen advisory groups; another testimonial comes from Kenmore Principal David McBride, who shared the following words with the SACIRSC. “When I reflect on how we succeeded in reopening schools and getting back on track, I can’t help but acknowledge the tremendous community support that the schools benefit from—even during this contentious year. Things could have been so much worse. Some deride “the Arlington way” as too cumbersome and taking too long—but remember the core to this concept is community voice, engagement and buy in. Think about all the beneficial actions that were taken because of ongoing dialogue among groups such as the IRC and the County. This is the key to Arlington’s success. And the great thing about this committee [SACIRSC] is that it gives voice to those that don’t always know how to navigate the system. In the end, the advocacy benefits everyone, because a healthier, smarter, stronger and more connected community makes it a better place to live for all.” Last week, I wrote that I am going through the end-of-year reports from various APS citizen advisory committees, beginning with the Budget Advisory Council. I'm sharing what I'm learning from these reports with you, along with some of my own questions and ideas. You can read the first part of my budget takeaways here. This week's budget email focuses on ways that we can improve community engagement during the budget process, plus one idea that might generate additional revenue for our schools. 1. We aren't getting the full benefit of the Budget Advisory Council's expertise. The Budget Advisory Council reports to the School Board and is charged with maintaining fiscal integrity, public confidence, and wise stewardship of taxpayer resources as outlined in school district policy. Although it reports to the School Board and not the Superintendent, the BAC could very likely play a more significant role during APS's budget development--and wants to. In its June 2020 end-of-year report, the BAC wrote: "Currently, the annual Superintendent’s Proposed Budget is prepared by, APS staff under strict secrecy and released to the School Board and the Arlington public on a planned date in late February. There is no statute, policy, or implementation procedure that dictates such secrecy." Because the BAC sees the budget at the same time it's presented to the School Board, it is "perennially concerned about its effectiveness as an advisor on budget issues and its value to the School Board." Additionally, The BAC notes in its 2021 end-of-year report that in the most recent budget cycle it had only about ten minutes to discuss its work with the School Board in an April budget work session—which doesn’t do justice to the extensive analysis it had prepared for the Board’s review and doesn’t incentivize talented and engaged citizens to donate their time to serve on the BAC. The BAC also wants to have more meaningful input into the Budget Direction that the School Board sets for APS staff each October. To that end, this year the BAC included its suggestions for the FY23 Budget Direction in its EOY report so that School Board members would have plenty of time to digest the recommendations and ask questions. 2. We can involve the community earlier and more meaningfully. Last November, the BAC offered to facilitate a meeting with representatives from many different citizen advisory committees to share ideas about developing the APS budget and finding cost savings. In its EOY report it notes, “Although there seemed to be some hesitancy about the cross-committee meeting and BAC playing a role in convening such a group, we would encourage the Board to repeat the idea gathering process next year and to formally end it with such a gathering, hosted by the BAC, for the benefit of all groups, so that all of the committees’ ideas can be shared and discussed openly.” The report continues: “While we believe larger changes will be needed, we urge the Superintendent not to spring these changes on the community for the first time in late February, but rather to tell the community that certain things are being considered, so that the community has time to weigh in and participate in the conversation, before large decisions are proposed and made.” To that end, we could adjust the budget development calendar so that the community has more time to study it and provide feedback. The calendar for FY23 budget development was approved by the School Board at its July 1 meeting, but let’s start talking about the next cycle. As I wrote back in March, many other local school systems provide more time for citizens to weigh in on the budget. A few examples: 3. We can change how the budget is presented so it’s more user-friendly and useful to the School Board and the community. Right now, there’s simply no good way for the public to read and understand the APS budget as it’s currently presented. People with the time and financial literacy skills needed to digest all the information are at a distinct advantage in advocating for programs and line items they care about--and that’s a real equity issue. Additionally, and as the BAC noted in its 2020 report, there's real inconsistency in how individual expenditures and proposed cuts are presented in the budget book. We should explore:

4. We should talk about setting up an education foundation. In its EOY report, the BAC suggests that we could increase financial support for APS by forging a strong partnership with Amazon and courting other corporate philanthropy. We should talk about whether this is something we want to pursue and study the examples of other communities across the country (and in Northern VA) who have done so by setting up education foundations. Education foundations are separate non-profit organizations that raise money for their local public school districts. There are more than 6,500 district education foundations serving 14,500 school districts across the US (National School Foundation Association). These organizations raise money from businesses, other foundations, and individuals and can help support more equitable spending and fundraising across an entire school division, when compared to fundraising that's done only at the individual school level by PTAs and other groups. In the DC metro area, Arlington and Alexandria are the only localities that don't have education foundations. Some examples to consider:

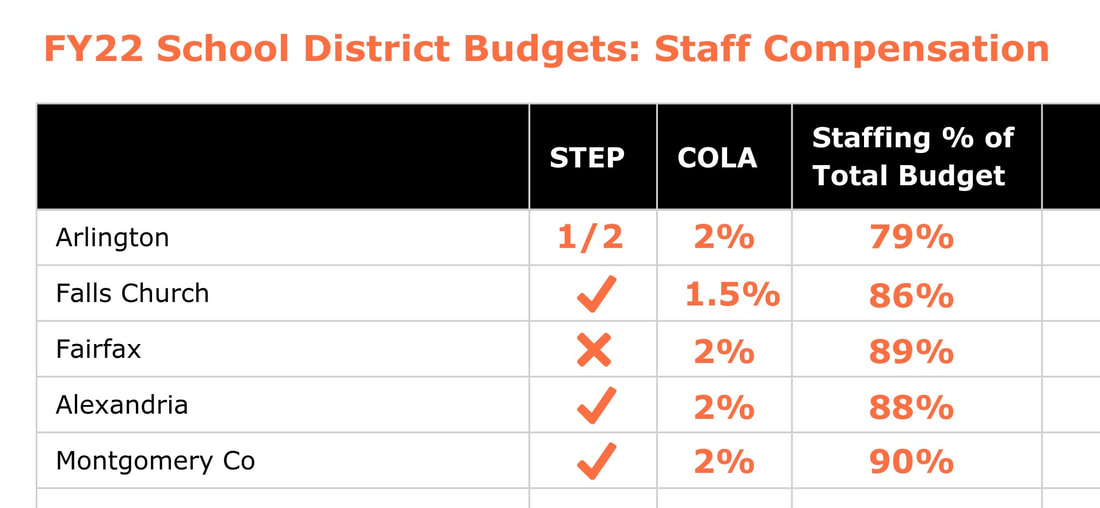

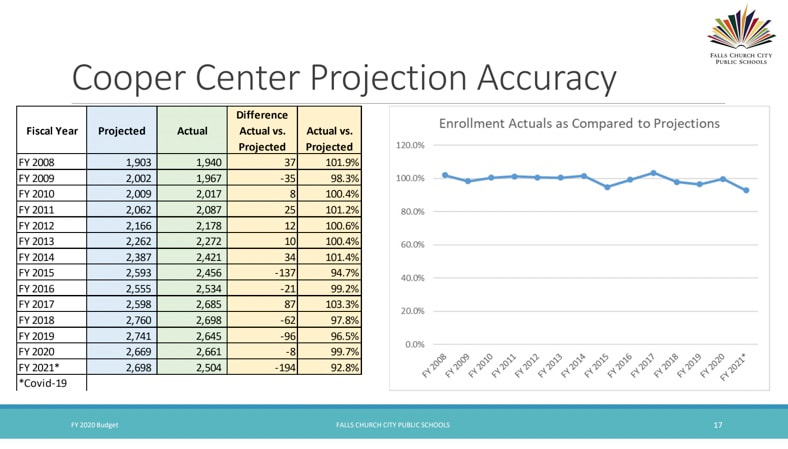

If you believe that Arlington could benefit from ideas like these or if you have ideas of your own to share, I invite you to get in touch with me, share and discuss this article with others, and become involved in the APS budget process. Early in my School Board campaign I received some great advice: a recommendation to read closely the end-of-year reports of the various APS citizen advisory committees. Community volunteers contribute considerable expertise and literally thousands of hours of work each year to collaborate with APS leaders and the School Board, and their informed perspectives are worth studying. As I continue to listen and learn over the summer I’m going through these end-of-year reports, starting with the recently published work of the Budget Advisory Council. I’ll be using these campaign emails to share highlights with you, along with my own questions and ideas. Why start with the budget, and why talk about it now? Earlier in the campaign I flagged the concern that APS is projecting a shortfall of more than $100 million by 2025. I think this merits a sustained and collaborative effort to ensure that our school system is on stable financial footing. Below are some of my reactions to the Budget Advisory Council’s end-of-year report, adding in my own study of the APS budget and investigation of how other local school districts develop their budgets. There's a lot to consider in the BAC's report, so I'm going to be emailing key takeaways in two parts--here's Part One. 1. We should talk about “zero-based” versus “baseline” budgeting. APS prepares its budgets through a method called “baseline budgeting” in which the prior year’s adopted budget is the starting point for building the next year’s budget. The previous budget gets reviewed and modified to reflect any necessary increases or decreases, and the resulting new budget line items are usually presented as a percent change up or down from the previous year. There are many advantages to baseline budgeting, not the least of which is the ability to easily track increases and decreases from previous years. However, it’s all too easy to carry forward items year to year without careful review and justification of expenses. For that reason, many school districts including those in Loudoun, Alexandria and Montgomery County use “zero-based” budgeting instead. LCPS describes its budget as “built based on actual needs without particular regard to previous funding.” ACPS notes that this requires staff to “scrutinize each line item and build their budgets from the ground up.” Given our projected shortfalls, building from the ground up—without assuming business as usual—sounds like it has merit. If APS can’t utilize zero-based budgeting, I believe it should consider more regular, formal evaluations of return on investment as other school districts are doing (what I described as “academic ROI” in my campaign platform.) 2. We should talk about “needs-based” versus “balanced” budgeting. One of the few differences of opinion I have with the BAC is its recommendation that the Superintendent present a balanced budget versus a needs-based budget, which has been the practice over the past few years. Without a doubt, it would be less painful for all involved if the Superintendent presented a budget that’s already balanced, but I think it’s the wrong move for two reasons. First, the Code of Virginia requires district leaders to develop needs-based budgets that reflect the total funding needed to operate schools. As ACPS notes, “It is then the responsibility of the School Board to balance the needs of the school division with the considerations of the economic and political environment.” The second reason to present a needs-based budget is that the community needs to understand the actual costs of operating its schools—and it deserves a voice as the School Board makes the hard choices that may be required to balance the budget. 3. We need to build in the full cost of staffing. Our budget reflects our values. If we believe that our staff is our greatest asset (and indeed, research confirms that there is no greater school-based influence on student achievement than access to a qualified, caring teacher), then our budget should reflect that by fully funding staff salaries. It’s wonderful that in its FY22 approved budget the School Board was able to fund a 2% increase for all staff and a STEP increase midway through the year. (If you don’t understand what a STEP is, see here.) Still, it troubles me that the School Board’s Budget Direction to APS leadership last fall included a waiver of its own policy that requires the Superintendent to include the STEP increase in each year’s proposed budget. (And this is not the first time this policy has been waived.) Why aren’t we building the full cost of staffing into our needs-based budget? Fully funding the STEP increase costs APS $10.6 million. Each 1% cost of living adjustment (COLA) costs $4.6 million. APS’s total approved FY22 budget is $700 million. I’m also curious why we aren’t able to fully fund the STEP increase when several other local school districts are doing so. Examples: 4. We need focused effort on, and transparent accounting of, enrollment projections. As the BAC noted in its report, enrollment projections are fundamental to building the budget. APS is continually working to improve the process by which it forecasts enrollment; it would be helpful, I think, for the School Board and the community to have a clear sense of whether those efforts are bearing fruit. When I looked at the Falls Church City Public Schools FY22 budget, I was struck by information that FCCPS included on the accuracy of its enrollment projections: Given how important these projections are to our budgeting, I’d love to see similar reporting included in our APS budget. (I believe I’ve seen something like this from APS before, but it’snot in the current budget and I wasn’t able to find it on the APS website.) If our projections are not as accurate as we’d like and/or not improving over time, perhaps we could explore working with different outside consultants to generate the projections.

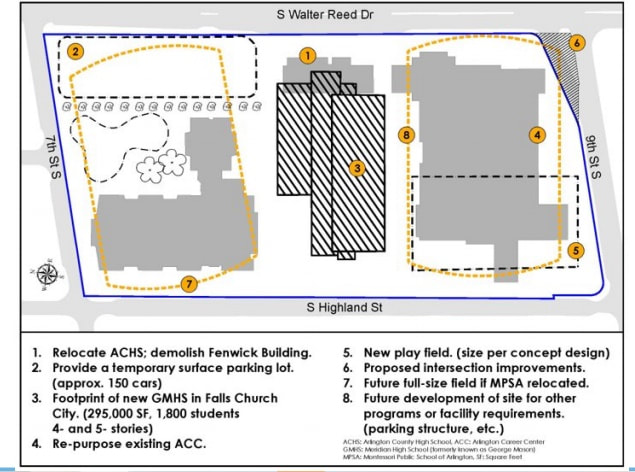

5. We need to look for cost savings in transportation, energy use, class scheduling, and more. Here I quote the BAC (and paraphrase what APS itself suggests in the FY22 budget): “With a projected deficit of over $100M by FY25, we need to start planning more than one budget year at a time, and we need to identify structural rather than one-time cuts that reappear in the following year’s budget. We should do serious studies on every one of the long-term budget savings ideas that show up in the Long-Term Savings Section of the FY22 Proposed Budget Executive Summary to determine whether there are real savings to be captured.” I wrote about Transportation in May and want to keep listening and learning to understand how we can become more cost-efficient and environmentally friendly. I’m also keenly interested in how APS energy savings might dovetail with Arlington County’s goal to become a carbon-neutral community by 2050. I also continue to believe that there are cost savings we can achieve by improving our class scheduling within existing class size limits. I wrote about this in March and in a January letter to APS, which also suggested that APS explore the idea of employing class size averages instead of a ceiling. (Some have used this to argue that I am in favor of increasing class size—which is not my position. I am trying to find creative solutions that don’t yield larger classes across the board.) Studies suggest that districts who increase their scheduling efficiency and/or adopt class size averages are saving tens of millions of dollars. In my next email, I’ll talk about a few steps we could explore to improve the budget process and format, plus one idea to increase revenue (no tax increases involved). Note: this information is current as of the May 25, 2021 School Board Work Session. On June 24, the School Board will vote on its latest Capital Improvement Plan (CIP). The CIP describes major capital projects, such as new schools and school additions, as well as major maintenance and minor construction projects. Normally, the CIP covers a ten-year time span and is updated and approved every two years. However, because of economic uncertainties created by the pandemic, last year the School Board approved a one-year CIP for FY2021, and this year’s CIP will only cover three years (FY2022-24). Beginning next year, we can expect a return to the normal ten-year cycle. The Superintendent presented his proposed CIP on May 6; working off of the Superintendent’s document, the School Board will present its own CIP next week on June 3. It will hold a public hearing on June 10 in advance of its vote to approve a CIP on 6/24. The three-year CIP currently under development proposes funding for a number of projects, including:

Under the plan, all Montessori PreK would move to this location and it adds a Montessori middle school program serving up to 175 students (71 of whom are currently at Gunston), for a comprehensive PreK-8 Montessori experience onsite. It also expands the existing Arlington Tech option high school program into middle school grades: up to 450 Arlington Tech middle school seats would be created. The number of full-time students enrolled in the Career Center’s various programs would increase from 513 (September 2020) to 1,400. And the number of part-time seats for CTE students from other schools who take a class at the Career Center would increase from 183 to 300. The Arlington Community High School students (usual annual enrollment is approximately 285 students) would be relocated to a site not yet identified. It’s worth noting that this program has been moved three times in the last 20 years. Including all the projects on the CIP wishlist would require voters to approve a $23.01M bond referendum next November and a $133.59M bond referendum in November 2022. It would increase debt service payments to more than 10% of APS's annual operating budget by FY2025--the same year that we are projecting a $111M gap between revenues and expenditures. It’s unclear whether the County would approve a move to exceed the 10% debt service ratio cap that’s been in place for some time. Because of this, APS has developed two CIP alternative scenarios as follows:

Here are the questions I’d like the School Board to ask, and/or the public to ask at the June 10 CIP public hearing: 1. If the critical shortage we’re trying to address is middle school seats (deficit of 703 seats by FY27-28), what happened to the design studies on expanding Gunston and Kenmore that were presented to the School Board in April 2020? Each would add more than 500 seats at a fraction of the cost estimated for Career Center redevelopment (Gunston = $50M, which could be Montessori MS seats; Kenmore = $20M). 2. None of the scenarios currently contemplated for the three-year CIP includes accelerated upgrades for HVAC--and in what APS is calling Scenario #4, funding for routine HVAC replacement is eliminated after Spring 2022. Given community concerns about ventilation and filtration in school buildings, is this wise? 3. Looking at the CIP through an equity lens: if we eliminate funding for all HVAC, roofing, electrical, and windows upgrades after Spring 2022, which schools will be affected? 4. What’s the line-item breakdown for the $14.24M needed for improvements at The Heights? At various times, this has been described as parking, stormwater management, accessibility improvements, and the need for a playing field. What are the specific costs related to each of these elements? In particular, what is the specific cost related to the accessibility improvements, which are essential? What would be the cost difference if APS leased parking at one of the many nearby commercial parking garages vs. constructing 64 general parking spaces underground? 5. A really critical question asked by Reid Goldstein in the May 25 work session: If we do all these things, how much funding do we have left for anything else in a ten-year timespan (like necessary renovations to our older and/or overcapacity elementary schools)? The answer right now is “We don’t know,” because we don’t have the County revenue projections for ten years out, which are essential to figuring out APS’s overall bond capacity. Those ten-year County revenue projections should be available next year, when we’re a little farther out from the pandemic. 6. What would redevelopment of the property containing ACHS, Montessori and the Career Center really cost? The $184.7M figure is likely low. Wouldn’t we like to know before we approve this CIP? There are several things I like about the proposed redevelopment of that property, not the least of which is providing needed relief for the 300+ students currently housed in relocatables and providing upgrades that will enhance CTE and Arlington Tech instruction. However, there are too many unknowns right now for me to feel comfortable forging ahead. It seems like it would make more sense to take one more year to vet this plan and include it in next year’s ten-year CIP. An additional year would allow us to answer the following questions:

I am also a little worried about approaching voters with a record-high $166.6M in bond referendums over the next two years in light of the frustration and anger that some members of our community are feeling about schooling during the pandemic. Arlington voters have traditionally been very generous about supporting our schools with bond funding, but this past year has been exceptional in many ways. Funding all the elements of the three-year CIP except the Career Center/Montessori/ACHS redevelopment would require only $48.42M in bonds in 2021 and 2022, which might be a more reasonable ask and might give us the time we need to answer the questions raised above. Over the past week, I've been texting and calling voters about the School Board Caucus. Among the many gratifying messages of support are a fair number of messages that are highly critical of my progressive positions.

These voters feel I should be "kept far away from schools and any elected role" because I will "indoctrinate" students with "anti-American propaganda." The "propaganda" in question is my belief that we have a moral obligation to ensure that ALL students feel safe, welcomed, and valued in their schools, no matter their race, religion, immigration status, gender, sexual orientation, or any other aspect of their identity. Yes--I believe that systemic racism is a real thing and that our students need to know how to understand, navigate, and improve a world that's been structured by racial division. That's why I have unequivocally called for the removal of SROs from schools and it's why I continue to push the Virginia High School League to adopt explicit anti-racist policies and penalties following the Wakefield-Marshall incident earlier this year. Yes--I believe that our LGBTQ students deserve safety and respect from their peers and adults. When my sister came out as gay during high school in the 1980s, there were no groups for gay students in schools and no official acknowledgement that LGBTQ students even existed. I now have a trans nephew who has been able to make his journey with the support of my phenomenal stepsister, other adults, and his friends. I am proud to support queer families like this one in our community. Yes--I believe that ableism is a real thing in our community and society at large. Who can forget President Trump's overt mocking of a disabled reporter five years ago? That's why I called on the School Board to hold APS staff accountable last year when not one, but two new school buildings opened without the necessary safety and accessibility measures required by the Americans With Disabilities Act. Yes--I believe in religious freedom. It's why I applaud APS's decision to change the school calendar starting next August so that we recognize and respect a range of religious holidays, including Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Diwali, and Eid Al-fitr alongside Christian holidays. Public education isn't perfect--we still have a ways to go in order to ensure that all students feel safe, welcomed, and valued in our nation's classrooms. But across the country, and even in progressive Arlington, there's a strong push to turn back the clock and erase the progress we've made. We have an obligation to every child. Every. Child. I hope you will join me in standing with all students and cast your ballot this weekend. Arlington’s 26 square miles are a honeycomb of more than 150 school bus routes and approximately 2,500 school bus stops (pre-pandemic). The majority of APS students are bus-eligible, but thousands walk, bike, drive, or are transported to schools each day in a family car or carpool. Transportation matters to me for several reasons. These include: 1. Cost: APS’s transportation budget is just over $22 million, or approximately $832 per student. Five years ago, the cost was approximately $650 per student. There are more than 3,000 parking spaces for staff and students on APS property, each of which costs between $15,000 - 75,000 to construct; in addition, APS leases parking for staff at some facilities. 2. Congestion: Nationally, 54% of school-age children are driven to school in a private vehicle, accounting for about 15% of traffic on the road during the morning commute. 3. Student health: Kids exposed to significant traffic pollution run a higher risk of developing asthma, other lung problems, and heart problems as adults. On the positive side, kids who walk, bike, or roll to school are generally more alert and engaged in learning during the day. 4. Climate: As a longtime local Sierra Club volunteer, I’m aware how our transportation choices (mine included!) contribute to climate change. As a mom, I worry about what climate change means for our kids. The transportation sector (within-County and through-County) is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Arlington. I think Arlington does a great job encouraging residents to use public transit, walk, and bike--for example, we are one of only 15 communities nationwide to be designated a Gold Level Walk Friendly Community. Arlington Public Schools is also working hard on the same front. In 2013, it launched APS Go!, a transportation demand management (TDM) program for the school district. The 2016 APS Go! Plan, even though it’s a few years old, is still a valuable read and many of its recommendations remain relevant goals for us to pursue. Additionally, APS participates in the national, grant-funded Safe Routes to School program to conduct projects and activities that improve safety, enhance accessibility, and reduce traffic and air pollution in the vicinity of schools. To support these efforts, APS provides families with resources like safe walk zone maps posted on each school website and a “SchoolPool” website that helps families form carpools, walking groups or biking groups. Additionally, the iRide program offers APS students a 50% discount on public transit via ART, Metrobus, and Metrorail. All of this is great, but we can make it even better: more efficient, more convenient, more environmentally friendly, and more cost-effective. Here are some suggestions: 1. Fully utilize school bus capacity. More than 16,000 APS students are eligible to ride the bus, but only about 65% of these students actually do so on a regular basis (again, pre-pandemic data). At the elementary school level, 40% of school bus trips occur under 50% of bus capacity. We could improve upon this by:

2. Teach transportation as a life skill to all students. Gillian Burgess, a member of the Advisory Committee on Transportation Choices (ACTC) comments: “We teach kids how to swim--and nobody’s going to swim to their job.” Gillian believes we should ensure that all kids know how to ride a bike and that by fifth grade, all kids should know how to use public transit. Gillian shared the example of another school system that teaches about transportation choices and then sponsors a scavenger hunt field trip for its fifth graders: each small team is chaperoned by an adult and must use community public transit to search for landmarks and other scavenger hunt items. 3. Use ART and other public transit options to bus kids to school, particularly older students. The iRide program is a good start, but we can do more. In Alexandria, for example, students ride free on DASH buses and there are no school buses provided for older students where DASH bus routes enable easy commutes to and from school. Washington, DC, has gone a step further and doesn’t provide school buses at all, except for students with disabilities, field trips, and school-sponsored trips to and from extracurricular events. DC’s students ride free on the city’s public transit, including MetroRail. I’m not arguing that we need to adopt DC’s solution, but we should certainly investigate when and how we could coordinate service with ART and WMATA and reduce fares for students. For example, I live on McKinley Road just a few blocks from McKinley Elementary. There used to be a Metrobus stop, and then an ART stop, right in front of my house. Those routes ran to the East Falls Church Metro, and both routes were ultimately cancelled because of low ridership. Next year, the Arlington Traditional School will move into the McKinley building. Twenty-five percent of ATS students are from lower-income families, some of whom will rely on public transportation to reach the school and participate in things like parent-teacher conferences and PTA-sponsored events. Restoring a bus line that runs along McKinley Road past the school would help ATS, and it would help nearby residents who had lost their public transit access due to previous low ridership. This is just one example of the ways that all community members could benefit from collaborative County-APS transportation planning and coordinated public transit service to schools and other destinations. If you believe we need School Board members who understand all the issues facing us over the next four years--including transportation--then I hope you'll vote for me in next week's School Board Caucus. Voting happens online May 17-23, and you can find more information about how to vote here. As I hope you already know, the Arlington Democrats are holding their School Board Caucus online next week from May 17-23. You’ll find the link to the voting platform, information about how to access in-person assistance from the Arlington Dems, and a brief video demonstrating how to use cast your vote online here.

This is the first year we'll be using an online platform to cast ballots and collect votes. Online voting will provide certain benefits, but it also raises a few thorny issues. I want to talk about one of those issues and explain how I plan to handle it. In any regular, non-COVID, in-person voting situation, we have safeguards in place to ensure that no voter is pushed into voting a particular way. Candidates, campaign staff and political party volunteers are able to campaign and distribute sample ballots outside a polling place, but they can’t walk in with you and stand next to you at the voting machine. In a world of online voting, however, this is now possible: a stranger can knock on your door, approach you as you leave the grocery store or the Metro, or engage you while you’re walking to the park with your kids. The voting machine is in their hands. They’re asking you to vote on the spot, and perhaps urging you to vote for a particular person. If you agree and take the mobile device to enter your personal information, there’s no guarantee that you’re even interacting with the official voting website--maybe this is a website someone’s created to look like the real thing. I think we’ve had quite enough voting- and election-related conflicts in our country over the past few years, and I have no wish to do anything that would raise a doubt in anyone’s mind about the integrity and validity of the voting results. That’s why you won’t see me or my campaign volunteers out during the Caucus with devices in hand, approaching strangers to collect their actual votes. I have encouraged the Arlington Democrats to add language to the Caucus Rules that would stipulate the following: Voters in need of assistance are encouraged to contact the Arlington Democrats, vote at one of the Arlington Democrats-sponsored in-person voting locations, or reach out to a trusted friend or family member for assistance. If a voter is approached by a stranger offering to collect their vote, they should decline, contact the Arlington Democrats to report the incident, and then proceed to vote as described immediately above. I am 100% in favor of efforts to promote broad participation in the Caucus and ensure that people without the means to vote at home have an avenue to do so; however, encouraging candidates and campaigns to collect votes is a recipe for coercion and intimidation, not enfranchisement. I am particularly concerned about how this might affect those with less privilege in our community and anyone who feels uncomfortable being approached in person during a pandemic. If we think it’s a good idea to go door-to-door with mobile devices in order to boost voter turnout, then this should be done by nonpartisan Caucus officials, not by individuals who have a vested interest in the outcome. So, May 17-23 you’ll see me and my team using every means at our disposal to ask for your vote--but we won’t be taking your vote, and I’m calling on my opponent to publicly commit to the same. I have tremendous respect for the Arlington Democrats, who do so much to advance the party’s ideals and turn out voters for local, state, and national elections; but I believe that having candidates standing by the ballot box sets a troubling precedent and is a misstep I don’t want my party to make. Across the country, there's been a lot of talk about how to support students as we recover from the pandemic and deal with its lingering impacts.

Drawing on my career in education, I know that there are some essentials we'll need to have in place in order to help all our students thrive. I also know that many of these measures would benefit students well beyond the period of pandemic recovery--and so I am hoping we'll make many of these standard operating procedures in APS. 1. Start with basic needs. Kids can't learn if their basic needs aren't being met. Those needs include food, shelter, rest, health care, economic stability, and secure relationships with trusted adults and peers. Schools, in close collaboration with other community organizations, have to ensure that the children in their charge are ready to learn. We can do this in the following ways:

2. Commit to healthy school culture. As we recover from the pandemic, we have an opportunity to do more than just "get back to normal." If we're honest, we'll admit that "normal" wasn't working for some of our students and that we can do better. Here are some things we can do:

3. Reframe "learning loss." I've been thinking a lot of about the term "learning loss" and its cousins, "achievement gap" and "academic deficit" and "struggling students." What do these terms have in common? They emphasize what students lack and ignore the strengths they bring. The blame rests with the student, not with the system. I thank Gabriela Uro and her colleagues at the Council of Great City Schools for introducing me to the term "unfinished learning," which I like much better. Why does our word choice matter? Because of the message it sends to our students about their value. Our kids are more than their reading levels, SOL scores, and end-of-quarter grades. Many have exhibited unbelievable amounts of determination, patience, and maturity during the pandemic. If we reduce them to a score on a standardized test or measure their "grit" only by on-time completion of a difficult assignment, we'll do them an injustice. Here's how we can address academics in a more thoughtful way:

For more on this topic, I recommend "Accelerating Learning As We Build Back Better" by Linda Darling-Hammond, writing earlier this month in Forbes. If you agree that our students deserve support like what I've described here, and you agree that we can do better than simply "getting back to normal," then I urge you to make a plan to vote in the ACDC School Board Caucus May 17-23. During this School Board race, I’ve urged voters to cast their ballots based on the full range of significant, long-term issues we need to address over the next four years.